There are many things we still don’t know about the Covid-19 virus. One is exactly how it spreads. But a consensus has emerged that outdoor spaces are safer than indoors. The worst possible environment is an enclosed, crowded one, perhaps with air conditioning or a fan. Far better to be outside, where wind and sun reduce the risk of transmission, and there is more space for people to be six feet apart.

Coronavirus has triggered sweeping changes to the way we live, travel and work. The implications for big cities like London, New York and Paris are profound, and policymakers are scrambling to understand how to respond while preventing an exodus of the businesses and people that are their lifeblood. The biggest question is how to create enough space for people to safely walk, sit and eventually eat and drink outdoors. More than ever, pedestrians are jostling for space on overcrowded pavements while roads lie empty. “People, not cars” has long been a clarion call for advocates, campaigners and designers fed up with the pollution and noise created by busy, multi-lane roads in the middle of cities. Now the changes they have lobbied for are suddenly a reality.

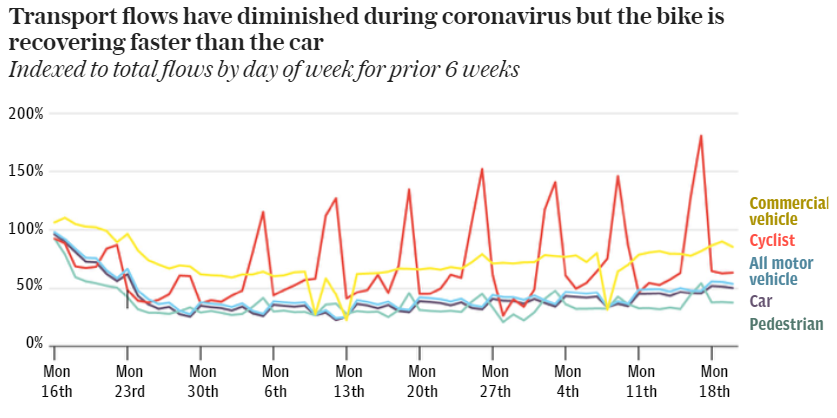

Thousands of new miles of bike lanes are planned in cities around the world with Paris putting in more than 400 miles. Cities including Athens, Tampa and Tel Aviv are planning “streateries”, closing roads and allowing restaurants to serve customers outdoors. Even in the US, where residents are famously wedded to their cars, cities including Denver, Minneapolis, and Milwaukee have closed streets to vehicles to allow more space for walking and cycling. Many of these measures are temporary but walking and cycling advocates hope they will become permanent. These projects now have the support not only of individuals but businesses, who want their customers to be comfortable queuing at a safe distance from each other, and who will also benefit from closed-off outdoor seating areas for restaurants. The signs are auspicious in the UK, with traffic-flow data showing bike use is recovering faster than other forms of transport in recent weeks. Transport flows have diminished during coronavirus but the bike is recovering faster than the car.

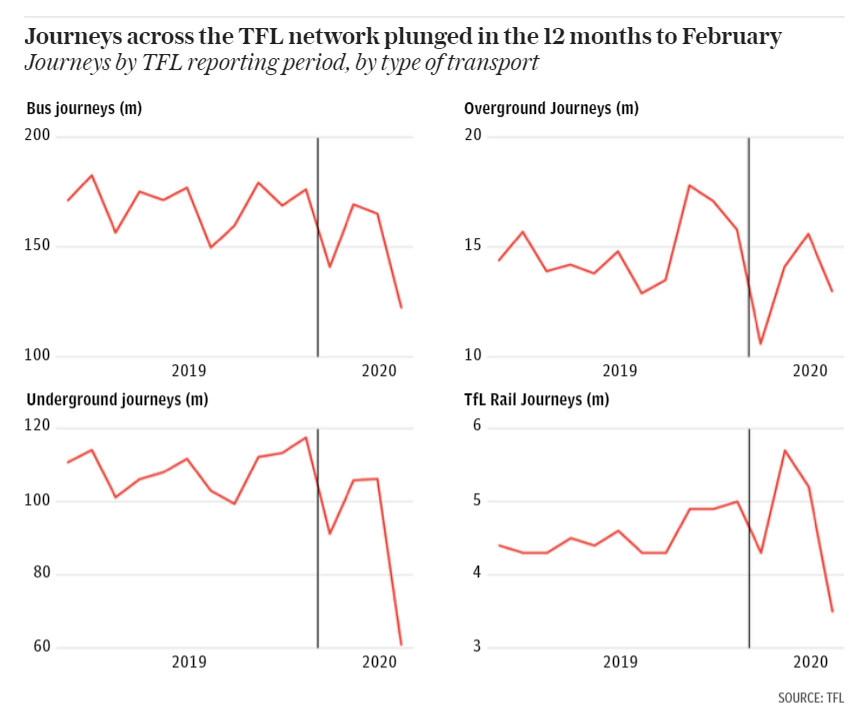

Under government plans, UK councils must rapidly transform their pavements to make it easier to social distance. Temporarily, this means traffic cones and emergency one-way streets. London is going further. In one of the biggest car-free plans in the world, streets between London Bridge and Shoreditch, Euston and Waterloo, and Old Street and Holborn will allow only buses, cyclists and pedestrians. Some roads will be designated for walking and cycling only. Will Norman, London’s Walking and Cycling Commissioner, said space on London’s red buses and the Tube is likely to drop to as low as 15pc to enable social distancing, leading to an urgent need to get people cycling. The city has already launched more temporary Santander Cycle hubs, or “Boris Bikes”,to cope with demand. “Last weekend was the busiest ever on Santander Cycles,” he says.The capital had already witnessed a plunge in usage of trains, tubes and buses due to coronavirus – and with bike use on the increase, the trend looks set to continue.

Among technologists, the sudden surge in pedestrianisation is vindication that bets on so-called micro-mobility companies – scooter and bicycle hire start-ups – could be about to pay off.

Micro in scope

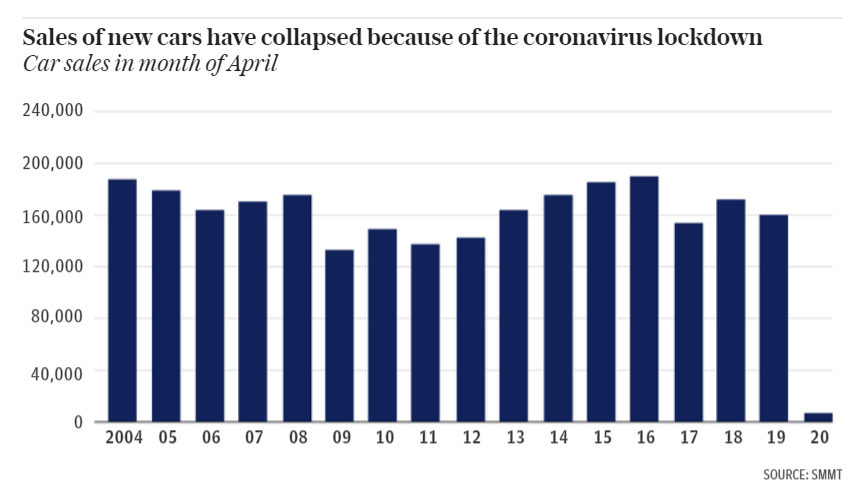

Martin Mignot, partner at Index Ventures who have invested in companies such as scooter company Bird, says: “People have been rushing to buy scooters and e-bikes. That is only going to grow in the next three months. Most people in London don’t own a car. The only option is get on a bike or get on micro-mobility.”Mignot says many of the trends were prevalent before lockdown, but with fewer people commuting or travelling long distances for leisure, something that might have taken years is happening in a few short weeks. In Peachtree Corners, a small city near Atlanta, Georgia, a pilot of remote-controlled scooters, which can be driven back to a cleaning and charging station between rides,had been planned before the pandemic, but now has extra relevance.“People will be even more inclined to get on an e-scooter that’s been disinfected than say, a subway or a bus or a cab,” said Brian Johnson, city manager. Europe is moving the fastest. In France, Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo had already been pushing the model of a “15 minute city”, reorganised with more retail, coffee chains,workplaces and greenery closer to where people live. The idea is that you don’t need to leave your block to do what you want, and if you do, you could cycle. There are threats to visions of a post-Covid car-free utopia. As people begin to travel to work again, will they really be comfortable taking buses and trains, where they must share air and space with strangers? These worries could lead to a surge of people getting back into their cars. Revenue from public transport could also dry up, leading to declining investment and quality. Data from connected car start-up wejo shows that across the US in April, passenger vehicle sales were down by up to 60pc for some models, and up to 20pc across the board. And in the UK, car sales plunged to a low not seen since the Second World War in April.

The company projects May sales of 700,000 in the US – half of what was sold in February. But in China, hit earlier by the Covid downturn, car sales have rebounded. “The private automobile is going to make a comeback because of people’s concerns about sharing space with other people,” said Anthony Foxx, chief policy officer at US app-based taxi company Lyft. There are also risks to the fast-paced, relatively uncontrolled way in which these projects are popping up. Consultations may be boring and tedious, but they let the Government figure out what the community wants and does not want.“We can’t just use it as an opportunity to get our own personal pet projects,” says Jascha Franklin-Hodge, executive director of the Open Mobility Foundation, which acts as a go-between linking cities and private companies. That means looking at where new pedestrianised zones, improved roads and bike lanes are planned. Are they just there to please the most vocal and politically engaged, or are they going to make cities a more pleasant place for everyone, including those living in poorer areas?“We actually have to examine our values and say ‘how can we build cities that are more equitable?’.”